Rail Engineer has previously published articles on cyber security, and it is a subject that will be undoubtedly covered many times in the future. Protecting data and keeping systems safe is still not universally recognised as something we should all be doing, and instances of hacking with damaging and often costly results happen all too frequently. It is necessary to issue and re-issue ever present reminders about the threats and how they can be spotted and managed to avoid business disruption or unsafe situations.

Railways in general are well aware of the risks involved, and most administrations do understand the broader measures needed to keep the trains running safely and the operational processes intact. However cyber attacks do occur, often because the circumstances are not perceived as possible, and the resulting loss of service can be very embarrassing.

A recent IET webinar given by Stefano Saccomani and Richard Thomas from AtkinsRéalis told of the ever-changing face of cyber threats within the rail landscape.

Known incidents

Three incidents were described and analysed:

- In October 2022, the train Danish operator DSB suddenly found that numerous trains were being cancelled. A crucial test environment provided by Supeo took down vital interfaces. The investigation found that a single failure of one system took down many other systems. A third-party supplier was the single source of failure and the risks had not been properly assessed.

- In August 2023, the sending of emergency stop messages in Poland brought 20 trains to a halt. The impact of these stops affected many other services, and the problem took six hours to resolve. The cause was the VHF train radio system, an open channel with no encryption, which had been accessed by outsiders. The radio documentation could be accessed easily, with very poor assumptions made that the system would not be of external interest.

- In December 2023, again in Poland, a supply chain software malfunction caused a denial of service that affected train services. The train manufacturer was aware of cyber threats, but the software did not perform as well as intended. There was a general lack of awareness of the software’s state, made worse by additional interfaces that provided entry points to the system.

These are just three examples of what can happen and impact on the operational railway, but other instances exist. More common is hacking of business services that promote train travel, sell tickets, make reservations and suchlike that interface with the travelling public.

The Digital Railway

A phrase that crops up regularly in technical articles is the ‘Digital Railway’. The term is banded about by many people who do not really understand what it is all about or what is involved. In the past, most railway applications were individual systems, for example radio, customer information, train performance and reporting, all without much connectivity.

With the demand for better information all round, much greater connectivity is occurring as part of the digital transformation, leading to a diverse architecture and an extension of existing architectures. There is a convergence of Information Technology (IT) and Operational Technology (OT) with new dependencies and more access points. Software-based solutions are commonplace, even before the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is being considered. All of this is a hunting ground for hackers, whether or not the intent is criminal or otherwise.

Regulation, legislation, and standards

As can be expected, a host of guidance documentation has been prepared to help and direct organisations into protection measures against cyber attacks. These are at an international, national and railway level. Locating all these and then understanding them can be something of a challenge but much of the guidance amounts to common sense actions. These may not always be obvious until they are pointed out. In all of this it must be remembered that cyber security is a challenge for all rail engineering disciplines and, as is explained later, it is the connectivity of systems that is creating the digital railway. This connectivity is the potential window for hackers to access systems and it must be understood to a much higher degree.

The Telecommunications (Security) Act 2021 enforced the need for providers of public electronic communications networks and services to take all necessary steps to prevent cyber threats from disrupting communications networks that are vital to the continuance of everyday business in the country. Ofcom has the duty to define the security requirements and to make sure that telecom providers take all necessary steps to comply. While initially aimed at the public telecom operators, the railway must be equally compliant in fulfilling the requirements of the Act. Since the advent of fibre optic cables and associated transmission, the telecoms arm of Network Rail has become the universal ‘pipe’ for many operational applications including signalling and electric traction control.

Internationally, the subject is led by the IEC (International Electrotechnical Commission) and specifically its group TC9 Electrical Equipment and Systems for Railways. The IEC has been in existence since 1906 so is well established in the field of electrical standards and safety. For cyber security, the document IEC 63452 relating to safety levels for rail operators and suppliers, is embracing cyber security work with a new document IEC 62443 entitled Railway Cyber Security Regulations being produced. It is expected this will be published shortly.

Nationally, the British Standards Institute (BSI) is co-ordinating and focussing these IEC documents for the UK rail applications. A committee is established to produce a guidance document.

In Rail, the Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) produces standards that impact on the whole industry and RIS 2700 RST gives guidance on the verification of control measures for engineering change to rail vehicles. From this, standard TN111 details types of cyber security control measures for rail vehicles.

Within Network Rail the document TS 50701 is derived from IEC 63452 and gives guidance for rail applications.

If you’re already confused, it wouldn’t be a surprise. Understanding the best means for protecting against cyber attacks can be time consuming and the available documentation is hard to interpret.

For rolling stock projects, it has been established that a separate assurance chain is needed from a regulatory viewpoint, hence the emergence of TN111. Rolling stock design and operation contains air gaps, in situ on board systems that link to the outside world, balise readers that link to the signalling system, and a multitude of radio and satellite links that give operational performance information. All these interfaces must be cyber assured.

Managing the IT / OT divide

Both IT and OT have different assurance regimes, but a number of systems have to understand and manage the differences. The focus for IT is confidentiality of data whereas OT requires integrity and availability. For both of these, the connectivity of systems using telecom and data linkage is vital to the business objectives of the railway and the interfaces that have emerged create the opportunity for security breaches and cause operational limitations. Some of the systems where conflicts of interest may occur are:

- Digital Signalling. Very rarely are such projects undertaken at greenfield sites. As such, the design of a project must be aware of security already embedded in existing systems and designers should beware of assuming that the existing security is both fit for purpose and safe. There is a need to establish a ‘road map’ to enhance and leverage security capability within the products being used to ensure the security of the eventual project solution. This will involve interfaces across many stakeholders, and it can be difficult to interrogate the security of different manufacturers. Expectations should be shared and agreed with every party at an early stage.

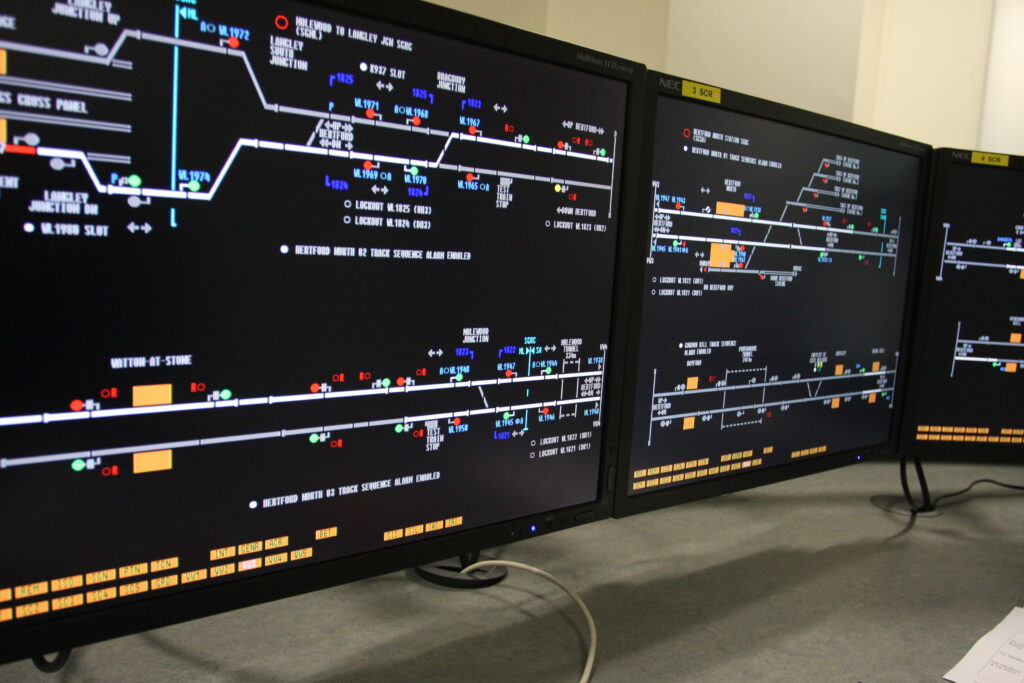

- Traffic Management Systems (TMS). To be effective, TMS must extract and assemble data from many sources, for example timetable data, train describer information, platform planning, rolling stock capability, train crew diagrams, and potential conflicting movements. All of these are vulnerable to cyber attacks which can impact on the resultant train plan. As such, there has to be a compromise between IT and OT that may end up recognising the vulnerability of the final information but without compromising safety.

- Driver Advisory Systems (DAS). Again, a number of inputs are required to produce the correct information as to the way a train is being driven. These include timing points along the railway, the current location of a train (derived usually from satellite positioning), train describer steps, train speed, and potential conflict with other train movements (this will be important for Connected DAS applications). These are all systems that can be accessed and hacked by third parties, and which represent an ever-present risk. It is therefore essential that DAS remains an advisory system and must never replace the information provided by the signalling system.

There will be other systems with multiple inputs that will impact on the business rather than the operational railway and can seriously affect the conducting of day-to-day business of selling train travel.

Future developments and monitoring

The current regulatory regime has been mentioned but increased regulation of cyber security for critical infrastructure is on its way. The EU National Infrastructure Security (NIS) Directive is already in being, and the EU Cyber Resilience Act is expected in 2024. Other countries as well as the UK are providing new regulation. These include the USA, Australia, Singapore, and the UAE. All this is fine, but does it further confuse the future situation?

From all of this, there is a need to improve incident reporting requirements and an identification of critical dependencies. Logging and monitoring must be better managed in order to recognise when something is not performing as expected. Vulnerability management must recognise that assets cannot be introduced, proved, and then forgotten. Asset life is also a consideration for railways, especially where systems and products are intended to last several decades. Regular security updates will be needed over the entire asset life.

Everyone has a part to play, and regular training on cyber awareness is needed. A positive and open reporting culture should lead to improved leverage and replication of best practice. As in safety practice, volunteer reporting of ‘near misses’ should be encouraged.

The way forward

Rail engineers will understand the V life cycle – requirements, development, design, build, test, integration, commissioning, maintenance, updates, and decommissioning. The V cycle tracks the interaction between these phases as a project progresses. Cyber security impacts on all of them and the people involved in each stage need to understand the risks that could arise.

Achieving this will secure some early wins so everyone should be educated to know:

- Security applies to all staff.

- Consideration of the whole life cycle.

- Establishment of a cyber security culture.

- An understanding of what is out there now and potential exposures.

- Investment in logging and monitoring and how it is practised.

- Knowledge on how to combat attacks and recover from them.

More specialised staff must be able to identify data flows, their direction, and concentrations.

If this sounds too generalised and impractical for everyone to take in, then put in place some realistic measures that will help the overall security. Carry out an exercise to create proportionate assumptions which could contain knowing what is most likely to ‘stop the railway’. Determine where the ‘crown jewels’ are, namely the critical elements of running trains and how they can be compromised. Be rational but be organised to manage the architecture of systems through constant live monitoring.

Some recommendations

Previous articles on cyber security have detailed the obvious steps to avoid being infected with unwanted intrusion: forbidding staff to use personal USB sticks or disks that might contain malware to access systems; not leaving computers switched on overnight in unmonitored environments; checking the credentials of people who have access to systems especially third parties brought in to carry out updates. It all sounds blindingly obvious but is often forgotten.

More focussed recommendations are as follows:

- Know your ‘bill of materials’ both hardware and software.

- Run ‘day in the life’ exercises and exercises to identify root causes.

- Know the difference between a cyber attack and a software bug.

- Work together to perform incident management.

- Understand the whole life situation including how to carry out patching and updating.

- Know the vulnerability of assets and have an obsolescence plan.

- Plan for graceful transitions.

- Ensure training and documentation is regularly updated.

- Set clear requirements and expectations.

- Understand how a recovery situation will work.

Some of you may find this all a bit much to take in and that is understandable. There will be a need to employ cyber security experts, and larger organisations should already have these in place. Smaller companies should have someone named for IT management and they will have responsibility for keeping systems safe. This might require calling in further expertise if problems occur.

Work on the basis that an attack will happen rather than believing you have the necessary steps in place and are safe from attack. Big organisations have suffered, for instance the British Library was attacked in 2023 with many of its processes seriously affected. Only now is it recovering from this.

There is no final solution as hackers are constantly finding new ways of accessing systems. Constant vigilance is needed. Above all, take the issues of cyber security seriously and don’t regard it as something that happens to other people.

For more information on cyber security, readers may like to refer to the following Rail Engineer articles:

- Understanding cyber security (issue 189, March-April 2021)

- Cybercrime and security in rail (issue 196, May-June 2022)

Lead image credit: Network Rail